Why not? With a fresh dump of snow smothering the wildflowers nearby, and no family obligations for the weekend, why not run down to the ominously named Purgatoire River and discover its mysteries for myself? A check on the weather cam revealed bare ground in La Junta and that was all the incentive needed, I threw backpack and camera in car, and away!

‘Away’ doesn’t accurately describe it – after an hour of driving I hit the town of Limon where a sign gives this cheerful warning: No services next 75 miles. Oh well. In for a penny . . . No services, but sweeping vistas of grasslands and farms provided plenty of scenery and the road was devoid of other vehicles almost entirely.

The Purgatoire River canyon, which, confusingly, is named the Picket Wire Canyon, more on that later, is most famous not for plants but for fossilized dinosaur tracks. The history of the river and its passage over time through the many layers of rock surrounding it is a fascinating journey in itself, and of course the underlying rock composition is one of the factors determining which native plants will survive in any location. As a shortcut to the plant part of this blog, later you can check out these explanations of the canyon’s geology, they are brief, with good illustrations, and written in common parlance:

One more short detour. The names caused me much confusion and deserve a brief explanation. A Spanish priest, honoring the loss of a group of men who went down the canyon and never returned, named the river El Rio de las Animas Perdidas, or The River of Lost Souls. French traders subsequently translated this into their own language as the Purgatoire River, for purgatory. OK. At last we get to Picket Wire. As a person who has built and repaired many miles of all kinds of fences for the purpose of keeping animals in or out, the combination of Picket and Wire made absolutely no sense whatsoever. But it wasn’t about a fence at all, it was instead the corruption of ‘pergatiore,’ by the English speakers who came later and heard ‘picket wire.’

A gravel road leads 16 miles across the Comanche National Grasslands to Picket Wire Canyon

From the paved, road sixteen miles of a gravel track lead through the Comanche National Grasslands to the Picket Wire Canyon. The Nature Conservancy classifies the entire Comanche National Grassland as a part of the Central Shortgrass Prairie Eco-region. I rolled windows down and was serenaded by meadowlarks the whole way. Native grasses carpeted the ground instead of the non-native agricultural brome so pervasive elsewhere. Thick stands of tree cholla, (Cylindropuntia imbricata) were covered in yellow buds.

The land stretched out on all sides as far as the horizon with no man made structures.

At the trailhead, glad to be on foot once more, I find the descent into the canyon steep but short, and at the bottom the world is redefined by vast expanses of flat land bounded only by distant rocky formations. The canyon floor is much wider than I had imagined. It’s hard to believe that a place so big can be so utterly quiet.

I knew it was too early to expect many plants to be in bloom, my only disappointment was the heavy cloud cover which kept the colors of both rocks and plants subdued. However, sprightly Physaria managed to shine in spite of dark skies. The willows along the river had yet to begin to leaf out, but several Astragalus species were making their debut.

A species of Physaria gives a cheerful welcome

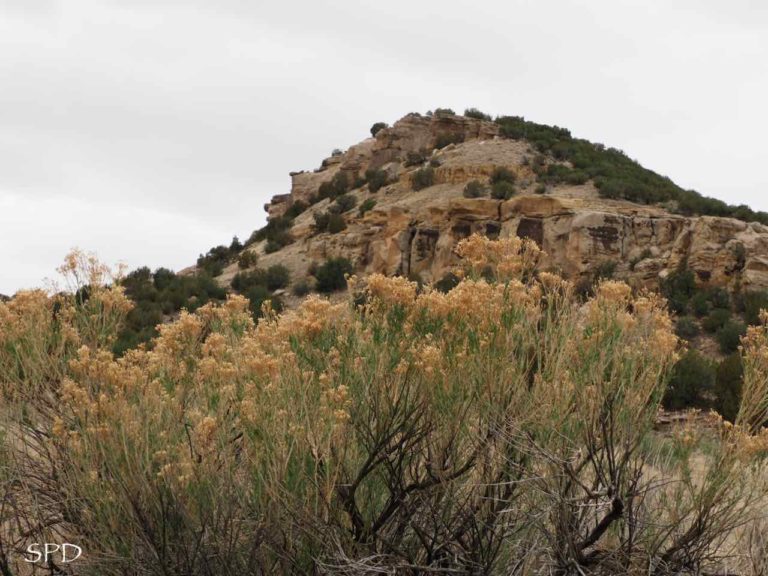

Grasses and cactus didn’t need blooms to be beautiful. The gracefully curvaceous seed heads of blue grama, (Bouteloua gracilis) are a favorite, they have a such playful air about them. Seed heads of rubber rabbitbrush, (Ericameria nauseosa) look almost like the new season’s blooms.

Rubber rabbitbrush, (Ericameria nauseosa) echoes the curve of hill behind it.

Top right: Echinocereus reichenbachii ssp. perbellus, Scrambled eggs, (Corydalis aurea)

Middle: Mountain springparsley (Cymopterus montanus), Brown-spined cactus, (Opuntia phaeacantha)

Bottom: Blue grama, (Bouteloua gracilis)

Two early Astragalus spp. and some native rock!

A blue heron heads for cover among the willows hugging the Purgatoire River’s shore.

Say’s Phoebes in Picket Wire Canyon. These birds are insect eaters, they don’t come to feeders.

In the Picket Wire canyon with dark skies stripping the rocks of color

Despite the 45 degree temperature, I am engulfed by fine snow showers from time to time. Walking the trail slowly and taking time for photos, I know I won’t reach the dino tracks this day, but I am satisfied with all I have seen already and by the opportunity to be immersed in this unique place, the scene of some history that is known, but also so much of what will remain forever secret. The quiet is pierced sometimes by the calls of grassland birds, I manage to catch a Say’s phoebe pausing ever so briefly as a flock flitters by. Grasslands and grassland birds are among the most imperiled of living things.

My own determination to help with conservation has been strengthened and renewed. Let’s keep everything we possibly can.

For a complete plant list and an excellent and through summarized description of the history and geology of the Comanche grasslands, I can recommend this piece written by Don Hazlett:

Vascular Plant Species of the Comanche National Grassland in Southeastern Colorado

Sue Dingwell

CoNPS Media Committee

We love to get your comments, scroll down to access Comment Box