In Nature’s Best Hope, Dr. Doug Tallamy has delivered a deep and powerful wellspring of inspiration for the many people craving an opportunity to be part of transformative change for our challenged world. Even more compelling than his first book, Bringing Nature Home, a seminal work in itself, Nature’s Best Hope is a clarion call for the informed appreciation of native plants and the immediate course correction of using them in our own planting spaces to form connected corridors that will help forestall the loss of species and ecosystem services that are we currently experiencing.

Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard, is a richly layered work, providing a contextual look at the evolution of our thinking about conservation, as well as detailed guidelines for getting started with native plants in your own nearby spaces, and, perhaps most importantly, the reasoning that will convince you, your neighbors, and your neighborhoods that now is the time to do so. Far from a dry treatise or an impassioned rant, the writing

reflects Tallamy’s character: cautiously optimistic, and gently but perceptively humorous. This book is an enjoyable read both for his fans, and for those who are new to his ideas about the roles native plants play in our landscapes. One of his stated goals was to write a book that would meet the needs of three groups of people: those who like plants, those who like animals, and those who like neither. He has done so.

Tallamy’s explanations of the specialized relationships among plants, insects, andanimals are fascinating stories, but also foundational building blocks forunderstanding the natural world we live in, whether we live in the city, the country, or anywhere between.

A white sphinx moth pollinates a flower while seeking nectar.

We must understand our pollinators’ needs.

Photo © Doug Tallamy, used with permission.

So many significant changes have come about in our world since the publicationof Bringing Nature Home. The words ‘monarch decline,’ ‘climate change,’ and ‘thesixth extinction’ are no longer strangers to our conversations but have become partof the common parlance. In his new book Tallamy has taken the opportunity toaddress some of the common questions that have surfaced during this interveningtime. Debates about the value of introduced plants and novel ecosystems; the feasibility of restoration projects, or the advisability of letting nature ‘take its course.’ These issues and more receive detailed and clarifying explanations.

A core concept of the new book is an idea Tallamy calls the Homegrown National Park, one that is created by us, as individuals, with no need for new laws to be passed. Tallamy in no way minimizes the extent of the challenges we face, he carefully quantifies all that we have lost in acres, in habitat, and in species, but his mastery of details is what makes his idea of the Homegrown National Park so compelling. He notes that we have witnessed time and again how quickly nature can restore itself and asks us to imagine how much

more quickly she would do so if only we helped her. We have the power as individuals to do so. The connected corridors of our Homegrown National Parks have the potential to restore some semblance of ecosystem function to more than twenty million acres of what is now ecological wasteland.” That is significant.

Tangible evidence of results, even in the most unlikely of places, provide welcome success stories: monarchs and native bees on the High Line in New York City, 103 species of birds in a tiny yard half a block from Chicago’s Kennedy Expressway, agrandfather and a toddler who are now loving and deriving the benefits of nature from time spent in their new, native plant, richly diverse backyards. When looking for specific advice within the book, highly visible chapter subdivisions make it easy to find exactly what you are looking for; there is a whole section on suburban yards.

Kirkland’s warblers are now so few in number that their future is precarious. We still have the power to reverse the decline of many plant and animal species. Photo: ©Doug Tallamy, used with permission

Another valuable feature is the FAQ section at the end. Just one example: in reply to the question, “Doesn’t this [planting natives] take more knowledge than the average homeowner has?” Tallamy replies in part, “In the 1980s we learned how to program our VCRs!” His full answer is more amusing and more edifying than time allows for here, but you can see how this section will be a handy reference for helping you answer the questions you will be getting, too. Toxic plants? Ticks? Yard’s too small? It’s too late to fix? Tallamy has you covered. Extensive illustrations, a comprehensive index, and a bibliography each add to the value of Nature’s Best Hope.

“Whether we like nature or not, none of us will be able to live long without it.”

In Nature’s Best Hope you will find the inspiration, the motivation, and the tools you need to help create our next National Park, it’s a positively electrifying read. Buy a book today. Or go to the publisher, Timber Press, and buy a box of them to share with key players in your life. I did.

Sue Dingwell

Master Naturalist, (FL & VA), Master Gardener, former Board Member of the Virginia and Florida Native Plant Societies, currently on the Media Committee for the Colorado Native Plant Society. This review is reprinted with the permission of Virginia Native Plant Society

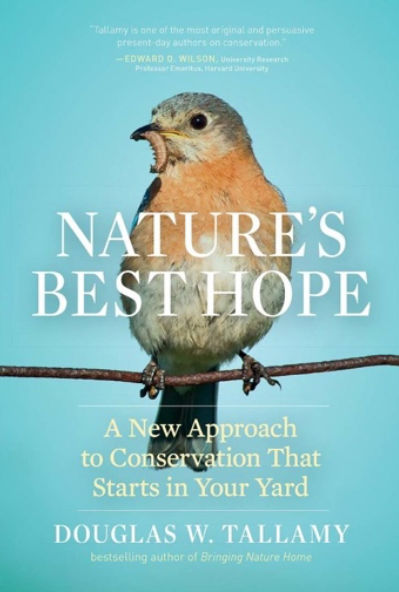

A bluebird returning to the nest with one of the thousands of insects needed to raise its babies. Ninety percent of insect species that eat plants depend on the ones they have co-evolved with and have a special relationship to.

Photo: ©Doug Tallamy, used with permission.