Yes, you can plant natives in containers! You can attract birds, butterflies, and native bees with them, too. And as you build your container garden you will also be contributing to the corridors of connectivity that environmentalists are trying to encourage everywhere. In all those fragmented landscapes where roads, buildings and parking lots have taken over habitat, you can be an enabler, helping to patch together pathways for natives, plants and animals alike, giving more space to live in and safe passageways to larger areas.

Native flowers, grasses, and vines grown in containers.

What can be planted

With containers you will have a lot of leeway in choosing which plants to use. The limitations usually arise from the amount of space you have and the amount of sun each container will receive. As a general rule, any native plant that is available to you in the commercial trade at planting time will be a good candidate, but always ask the seller if they have experience with container-growing the specific species you are interested in. Because you will have to provide regular irrigation, you can use some of the more water-loving species, such as swamp milkweed. All the plants recommended in our Low Water Natives brochures can be grown in containers. Grasses work really well. Trees and shrubs can be grown in containers, too, more on these later.

Here is my experience with natives in containers

My balcony has good morning sun on one side and only a few short hours of afternoon sun on the other side. You just have to experiment, plants really try to get along in the places you put them. Photos of some plants I have had success with, along with explanations, are shown below.

Aesthetics

Here we have to do some re-thinking of expectations. We have become accustomed to seeing our containers in continuous bloom all summer long with plants like geraniums and petunias. But those plants come from South Africa and South America, respectively, where plants have a long season to fulfill their life span and produce seed. Here in Colorado, our growing season is much shorter, and our natives have adapted to reproduce more quickly. In our native gardens, whether they are in containers or not, we want to include plants that bloom in early, mid, and late summer. This benefits not only the visual display, but also the pollinators, birds, and other creatures we are attempting to support.

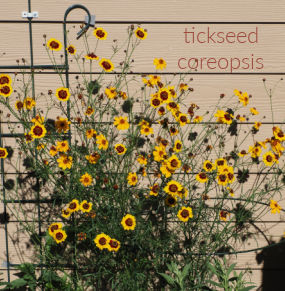

Container-grown tickseed coreopsis attracts a northern crescent butterfly.

Anise hyssop, Agastache foeniculum, scented blossoms and leaves are enjoyed by humans and mobbed by pollinators.

So how do we plan? One solution that works well is to keep each species separate and then situate the containers to feature the plants that are blooming the most prolifically. Most of us who are interested in containers are dealing with limited space, so there is not a lot of moving involved, just some minor adjustments. Having a single species in each pot means that their care can be tailored exactly. And because each container holds a limited number of plants, the bigger impact of single-species blooms gives the most satisfying display in my opinion.

Little bluestem, Schizachyrium scoparium, will mature and produce seedheads in one growing season – this container was started with three small plants in May.

Including natives with interesting texture and seedheads will add to your aesthetic impact. Fringed sagebrush and silver wormwood are perfect for this. Grasses are another wonderful addition. Little bluestem will reliably grow to three feet in one season from a from a four-inch pot. In fall the foliage turns russet and the seedheads are beautiful. Blue grama is another lovely addition, those graceful, curvy seedheads floating above the foliage are eye-catching as long as they are left in place.

Several guides for blooming times can be found on our website:

Gardening with Natives:

Check there in the Low Water Guides for your region and in the Ten Steps to Pollinator Garden.

Containers

Size matters. Don’t bother with containers less than 15 inches deep unless they are little tabletop-type arrangements with naturally small plants. Good drainage is a must. Research has shown that gravel in the bottom of your containers impedes drainage, just use leaves or pine needles at the bottom to keep the soil from leaking out through the drainage holes. Use saucers under your pots, the water that drains through will stain your flooring whatever its type may be. By using saucers you will also have reliable evidence that your irrigation is reaching all the to the bottom of your container, which necessary to promote deep roots. Size and drainage may be the two most important considerations in choosing a container.

I use a few terra cotta pots in my front entranceway, but prefer not to use them anywhere else. In freezing weather they are susceptible to cracking. They are also heavy to move around, and they tend to dry out faster than the plastic ones in our arid heat. These days, you can buy reasonably good-looking fakes at the box stores, and these have the advantage of being substantially less expensive and much lighter.

Watering

Water is a critical issue. In our hot, dry summers, containers filled with wildflowers and grasses will most likely need irrigation nearly every day. Those native plants you have put in pots are just not in their native environments and will require more attention than if you’d planted them in a natural area in a landscape. You must commit to the idea that watering will be a daily necessity. The only days I find my containers not wilting without a drink in July and August are the days that are slightly cooler and have cloud cover. Also, do not make the mistake of thinking a summer ‘rain’ will be sufficient. Unless we are experiencing rains heavy enough for flooding, your container will not get enough water to reach the roots in a typical summer shower. Mulching helps keep soil cool and limits dehydration. Drip irrigation on a timer works well, but still needs monitoring.

.

Soil and Fertilizer

For containers, the best choice for soil is a good potting soil. Most of these have at least a little fertilizer in them, but this is OK. Because you are watering so much, your natives will need a little extra boost. Potting soil is also lightweight which is another advantage. If you choose to make your own, start with one gallon of commercial garden soil which will contain no weeds, pests, or diseases. Then add one gallon each of coir, coarse sand, and perlite. You want your mixture to be loose enough to drain well, you can adjust the amounts of coir and perlite.

No to peat moss

- It can never be sustainably harvested, peat in bogs builds up at about 1 mm/year. And peat soils sequester huge amounts of carbon.

- Peat is hydrophobic and is hard to wet once it dries out.

- Peat is so acidic that it provides almost no nutrients for the plants.

- Peat is sterile and antiseptic, so it kills the soil microbes, and our native plants need those microbes for good development

Examples of container-grown wildflowers and grasses

These are all plants that I have grown in containers sucessfully, and are also ones that are readily available, with only a little bit of luck! In alphabetical order by common name:

Anise hyssop, Agastache foeniculum; Black-eyed susan, Rudbeckia hirta; Blanket flower, Gaillardia aristata; Blue grama, Bouteloua gracilis; Chocolate flower, Berlandiera lyrata; Clematis, (Western virgin’s bower), Clematis ligusticifolia; Fringed sagebrush, Artemisia frigida; Little bluestem, Schizachyrium scoparium; Mountain sneezeweed, Helenium autumnale; Rocky mountain bee plant, Cleome serrulata; Rocky mountain penstemon, Penstemon strictus; Sideoats grama, Bouteloua curtipendula; Swamp milkweed, Asclepias incarnata; Tickseed coreopsis, Coreopsis tinctoria; Wine cups, Callirhoe involucrata.

Trees and shrubs

All you need is a big enough container, time, space, and the willingness to know that their lifespan in a container will be shorter that of the same plant living in the ground. The bigger your container, the longer your tree or shrub will be able to live there. You could also hold a woody plant for a few years in a container and then plan for a permanent location somewhere in your landscape or in a community. Your woodies will not need to be irrigated every day, once a week will likely prove to be sufficient, twice at most, during times of higher heat stress.

Overwintering

This is an area with a lot of unknowns. The general recommendation for overwintering potted perennials is to provide a place sheltered from the extreme low temperatures we routinely get in many parts of Colorado. Garages would be perfect. In my house, garages are only for bikes and cars, so I have done some experimenting. I could not keep little bluestem alive over the winter even putting it in a corner of the covered porch where it was surrounded on two sides by a wall and on two sides by other pots.

Having been advised when I purchased it that the roots of our native clematis vine would need protection in winter, I duly wrapped the pot in a thick blanket and placed the whole thing inside another, bigger container. Then the spring rains came. I forgot to put a drainage hole in the bigger pot. It drowned. On the other hand, with no protection at all the Rocky Mountain penstemon, Fringed sagebrush, and Swamp milkweed all came back fine. Seeds of two annuals, Rocky Mountain bee plant and anise hyssop came up with great vigor wherever they had dropped in the fall.

Conclusion

Growing native plants is not only possible, but it is a source of great joy. Each morning there is something new to observe, each change an opportunity to learn something new. As the leaves and flowers spread and blossom, colorful, vibrant, and sometimes strange visitors come calling to your mini refuge. Try it, you’ll like it!

Photos below were all taken from my container-grown plants ~

Sue Dingwell

Co-webmaster

Colorado Native Plant Society

Master Gardener

Master Naturalist

Tickseed coreopsis was the longest blooming flower in my trials and drew a wide variety of pollinators.

The small clematis vine planted in May had reached seven feet by summer’s end. It began to flower late in the summer. Roots need protection over the winter.

Close up of an anise hyssop blossom feeding a native bee. These annuals re-seed freely and transplant very easily. Lovely scent to both leaves and flowers. Terrific pollinator magnets.

Fringed sagebrush with Rocky Mountain penstemon finishing up in back.

Swamp rose with silver-spotted skipper. This might be my most favorite flower – the scent is heavenly. Definitely loved by the pollinators.

Chocolate flower, yes, it does smell like chocolate – in the morning before it gets hot. Such interesting buds! It is a sprawler, will hang over edges.

Wild bergamont, wild about this color!

Sneezeweed – does not make you sneeze! Was used long ago as a snuff. That would make you sneeze!

Winecups, give this room to sprawl and fall.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks