“I have moonwort madness,” explains Steve Popovich, “Botrychulosis. It’s an incurable disease caused by a passion for moonworts.” After listening to his interview on a recent ‘In Defense of Plants’ podcast, it was easy to understand what that passion was all about. Moonworts, in the genus known scientifically as Botrychium, have some pretty mind-blowing characteristics. Steve’s longtime fascination with moonworts led him to discover a new species, Botrychium furculatum, wishbone moonwort, which turned out to have its own unique properties. Steve also had the honor of formally describing the new plant scientifically, a process that takes many years, and his work was published in the American Fern Journal last year.

Botrychium furculatum, wishbone moonwort, recently discovered and described by Steve Popovich and his colleagues. Photo courtesy of Glen Lee

Moonworts have been known and written about since Roman times. Tiny, somewhat bizarre looking, and with much of their life cycle hidden underground, by the Medieval ages people assumed these organisms came out by moonlight, and ascribed some imaginative curative powers to them. Moonwort was said to have the power to pull the shoes off a knight’s horse as it ran through a field, the spores of moonwort, when blown through a keyhole could unlock doors, and even render people invisible. What the plants really do is almost is almost as unbelievable!

Those crazy little moonworts can spend years underground, they can complete an entire life cycle down there without ever coming above ground. When they do rise from the deep, they are very ephemeral, you can only see them for a couple of months in mid-summer.

For an accurate ID of wishbone moonwort here in Colorado Steve had this advice, “The characters needed for the most confident identification are best expressed for only about a month or six weeks in Colorado, at peak sporulation when the sporophore is fully elongated.”

No wonder they were considered mysterious. Now we have knowledge and tools that help explain some of the mystery of these plants, but open up new realms of questions in their place.

Botrychium are fern allies, like ferns they don’t have flowers. They do have spores but they are only distantly related to ferns, and, says Steve, “Don’t say frond. They don’t have fronds!” What they do have is a complex relationship with mychorrizal fungi. Root hairs? Don’t need them! They can presumably receive all the nutrients and water they need from fungi to stay alive stay alive and to reproduce underground for years at a time.

A moonwort spore finds its happy place somewhere down between the mineral and organic horizons though exactly what other conditions it requires for germination is yet another unknown. Once germinated it grows as a gametophyte, lounging around in harmony with the mycorrhizae for years until one day it decides to reproduce. It has formed eggs and sperm, held in special places, and the sperm kind of swims through the soil and fertilizes the egg of the same plant, or sometimes a nearby plant. Crazy!

The fertilized egg (zygote) is now a sporophyte, and the moonwort, still underground, grows by mitosis, cell division, eating its former gametophyte for lunch.

Since they exist where no heliotropic signals are reaching them, it is an open challenge to figure out what genetic cue next causes the moonwort to move upward or even to know which way is up. When they do break the surface, they send up a single leaf, initially as only a stalk (petiole) only half an inch to two or three inches tall which undergoes yet another mysterious genetic cue. It now divides into two parts, one vegetative, the trophophore, and one reproductive, the sporophore, which holds little sporangia like a tiny bunch of grapes – the genus name Botrychium is derived from the Greek ‘botrys’ which means ‘bunch of grapes’ – these are cases that hold the spores. So a single leaf has become the bearer of two separate parts, almost like two separate organs.

As if that weren’t amazing enough, the moonwort can also reproduce vegetatively by forming clones that come out below ground near its roots, self-contained and perfect, ready to become another sporophyte plant.

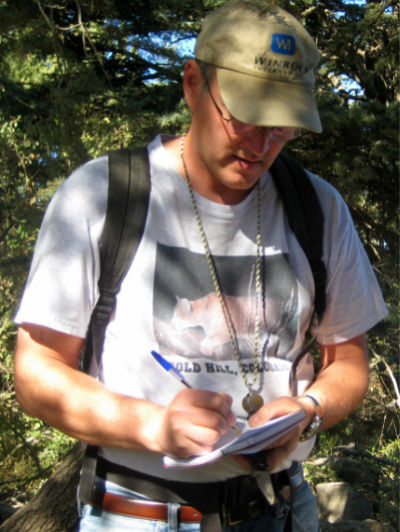

Steve Popovich collecting data on Cedars of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) in Lebanon’s Tannourine Cedar Forest Nature Reserve during a 2011 international assignment to determine why the trees were dying. The Cedar is the country’s national symbol. Steve was the Field Studies Cordinator for CoNPS for over ten years.

Photo courtesy Roger Rosentreter

At the point where the stalk divides, the new formation resembles a Y or wishbone shape. The new species of moonwort that Steve discovered exhibits a particularly bowed shape there, which is how it earned the name Botrychium furculatum; furcula being the Latin word for ‘little fork.’ And logically then, the common name, wishbone moonwort.

Here a brief pause in the story to bring the podcast itself into focus. Called ‘In Defense of Plants’ and hosted by Matt Candeias, it constitutes a bright spot in my week for sure. Matt interviews botanists, ecologists, restoration artists, and all manner of people engaged in the world of plants. In addition to the learning, it’s such an uplift to listen to two people rapturously and unashamedly enthusiastic about their subject, and not shy about declaring the importance of plant’s role in the world!

For instance, here’s a bit of what Steve had to say. Born to botanize, he was collecting leaves and fixing broken twigs before he could walk. However, he chose to major not in botany but in Range Ecology

because of the holistic and balanced set of courses required, the study of soils, climate, ecosystem management and more. Those courses demonstrated how all the parts of an ecosystem worked together and how important plants were.

“There’s bedrock and there’s soil and then there’s plants and everything green, and everything else comes from that – habitat, wildlife, birds – everything.”

That sentence resonated with me down to the very core of my being!

When Matt asked about the need to conserve moonwort, Steve said that U.S. Forest Service has created their own set of guidelines for conserving them. Thinning or fire is not a problem for moonworts, in fact they are often found in sites recovered from a disturbance but not yet closed over with canopy. But because of their critical relationship with the mycorrhiza, disturbance of the ground should be avoided, cracking breaks the hyphae apart. Steve noted that the mychorrizal fungi is turning out to be more connected with higher level plants than we ever thought possible; he speculated that moonworts could become a kind of canary in the coal mine as indicators of soil health. Also, that while the most common of moonworts are of course the most usually seen, any place that shelters the common ones may also harbor a few of the more rare ones.

Steve and Matt both agreed that each and every plant has its own intrinsic value in and of itself. Each plant has its place in the ecosystem, and we can’t put a human value on it. But in addition to that, we have no idea how something as small and seemingly insignificant as a moornwort could also hold great utilitarian value. What if we could figure out the genetic cuing a moonwort uses to learn how to turn on and off cell division in the fight against cancer? “We don’t know what we could possibly learn from any one plant,” mused Steve, “if we understood the nuances it has developed while learning how to live, doing things its own way.”

Out of space for one blog! In the podcast, learn so much more! ~

- How the discovery of wishbone moonwort led to the further and important discovery of its missing parent.

- Discover a lab in Iowa that specializes in moonwort genetics.

- Locate a key to Botrychium with line drawings for many couplets! It took ten years from inspiration to publication.

- Learn about a refrigerator experiment you can do at home. Though it does involve taping your frig shut for a year.

- Increase your knowledge of botanical terms.

- Learn about Horizontal Evolution!

Thanks to Steve for his generous help with this blog, especially for providing the photos, all the text for their captions, and editing for accuracy. His many credits include work for our U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the USGS Bio Resources Division, not to mention many humanitarian aid assignments related to wise use and conservation of botanical resources in third world countries – Tajikistan, Albania, Project Tiger in India, Nepal-Tibet, Bolivia, Nigeria, El Salvador, and others. Write a book, I said. Someday, he said.

Podcast – In Defense of Plants: Moonwort Madness

On hands and knees with glee! Flagging moonworts at a 2016 workshop field day, Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park, Saskatchewan, Canada. Steve says these get togethers are a great way for botanists to consort and party, bringing people together. He asserts that all is right with the world in that moment!

Photo courtesy Don Farrar

Peter Root at the 2005 Colorado moonwort workshop, considered Colorado’s first “moonwort aficionado,” and who trained and inspired many to search for these cryptic species.

Photo courtesy Andy Kratz.

Botryhchium lunaria, the type species for the moonwort genus, illustrating the characteristic half-moon shaped pinnae. This is one of the few moonworts that occurs in Europe. In North America it occurs in Greenland and northern Canada, while it is replaced by recently-described B. neolunaria in much of the rest of North America. Photo credit Wikimedia Commons.

Sue Dingwell

Media Committee

Colorado Native Plant Society

Botrychium campestre var. lineare, prairie moonwort, from the high mountains of Colorado, showing characteristic strap-like divided pinnae. In Colorado many plants have highly furcate pinna divisions, especially of the lowermost pinnae, and a more robust expression than plants in the rest of its range. Photo courtesy Kevin Kovacs.

Herb and Florence Wagner, pioneers in the advancement of Botrychium taxonomy in the 1980s and 90s, and who left their legacy in others carrying on. Glacier Nat Park, 1998. Photo courtesy Don Farrar.

Steve Popovich, left, and moonwort authority Don Farrar, right, hosting a Botrychium workshop in 2005, Mt Evans, Colorado.

Cindy Johnson at the 2005 Colorado moonwort workshop, retired professor from Gustavus Adolphus College, who has advanced our knowledge of below-ground ecology of moonworts and of site monitoring. Photo courtesy Andy Kratz

Nice blog Sue! These interesting and overlooked plants continue to receive attention disproportionate to their size! I encourage Colorado botany enthusiasts to look for moonworts in our mountain meadows and forest openings above 9000 feet, perhaps as a side-search while observing our beautiful wildflowers. Look for associated species solidago, pussytoes, rock jasmine, strawberries, and recruiting conifers knee- to head-high, in herb-graminoid forest openings and meadows, especially areas that have been historically disturbed 20-60 years ago but are now stabilized like roadside shoulders, old mining areas, and burned areas. Weber & Wittmann’s 2012 Colorado Flora has a good illustrated key. I can’t wait until next July to resume the hunt! If you find them let us know!

Thanks so much, Steve, and thanks for all your help. We will start a page on the website next spring where our folks can list their finds. Will also be looking forward to a blog featuring some your humanitarian conservation work in other countries!

Thanks, Sue! Loved this blog post. I’ll be on the lookout for these fascinating plants next year!!

Mary, thanks for taking time to comment! If anyone can find this little guy, it’s you!

Peter Root first showed me moonworts while we were surveying the Pikes Peak Highway from top to bottom for rare plants. Sort of like a little treasure hunt trying to find them, and they really look unusual. I remember Peter saying that some moonworts are probably not that rare, they are just small and hard to see, which is the case with a few common species. There is still so much to be learned and discovered about moonworks in Colorado and the Rocky Mountain West!

Thanks for your comment, David; and of course you’re right – there is still so much to learn. Here’s hoping we can keep it all around long enough to do so. How fortunate for you to have Peter Root as your mentor!